FOR ALL THOSE WITH AN INTEREST IN BRITISH INDIA STEAM NAVIGATION (BI)

BI History

These pages are the basis of a series to be added from time to time recounting some of the history of British India Steam Navigation. This opening page carries a potted history of BI from its formation in 1856 to the centenary year in 1956, when this account was published. A PDF version of this file is available for download here.

NEW! Shop here for BI memorabilia and giftsOther history pages: Timeline | Companies | Routes | BI News | Mercantile Empire | BI/P&O Merger document | Gairsoppa & Mantola | Dara wreck | Rohilla disaster | Rohilla Centenary | Calabria | Abhona trials | E Africa Shipwrecks | Today in History

A SHORT HISTORY OF

BRITISH INDIA STEAM NAVIGATIONIT IS admitted by her friends, her rivals, and even her enemies, that the experience of Great Britain in the maritime affairs of the world has been unique. It is simply a fact of history that the shipping lines based on that small island in the Eastern Atlantic are remarkable in strength and efficiency, these qualities rooted deeply in the natural instincts of an insular people with a long history of stable government behind them.

It is therefore an occasion of true international importance when one of the largest and oldest shipping concerns in the world celebrates its Centenary. This occurs in the autumn of this year, 1956, when the British India Steam Navigation Co Ltd — so much better and so affectionately known as BI — celebrates its hundredth birthday.

The occasion will be duly marked by appropriate celebrations in London, Calcutta and other bases of this fine old shipping line. It is more permanently memorialized in the Official History — BI Centenary, by George Blake, the novelist and maritime historian, and published by Collins of London and Glasgow at 21s.

It is a truly romantic story, fit for the pen of an experienced novelist, throwing into high relief the personalities of many remarkable men of the pioneering type, the dramatic growth of trade by sea in Eastern waters, the many dangers — and occasional comedies — of seafaring. and the intrusion of the steamship into ports that had never before seen anything more advanced than an Arab dhow or a masula boat. Historians of the future will see clearly that the development of BI from small beginnings was (however one may care to look at it politically) a phase of world history.

Mackinnon and Mackenzie

The founder of the company was William Mackinnon. He was born, in 1823, in Campbeltown. From this small seaport on the western coast of Scotland he went to Glasgow as a young man and there became familiar with the ways of Eastern trade in the office of what was then called an "East Indian Merchant." The facts cannot now be known with certainty, but it is on clear record that William Mackinnon arrived in India in 1847, and that he was immediately in touch with another native of Campbeltown, Robert Mackenzie. It is said that Mackenzie persuaded the young Mackinnon to come to India and seek his fortune in that rich and rapidly developing country.

However that may be, these two young Scotsmen ultimately formed a partnership as general merchants. Mackenzie was in business at Ghazipur, buying and selling all. manner of goods from Europe and exporting the products of India. (It is of much interest that he used the inland waterways of the Ganges delta for the collection and distribution of his wares). Mackinnon started as manager of a sugar mill at Cossipore. Soon they were working together in import and export trades, and thus was formed the firm of Mackinnon, Mackenzie & Co which was to become one of the greatest names in the commercial records of India.

It was not long before these two young men from Scotland saw that their trading interests could be extended by the use of ships, and they duly bought or chartered a few small sailing vessels to carry goods to Australia, then rapidly expanding as the discovery of rich deposits of gold was attracting immigrants from the United Kingdom. These settlers could absorb almost any amount of consumer goods, and the partners in Calcutta set out energetically to supply the demand.

This trade was so profitable that in 1853 Robert Mackenzie himself set out for Australia to oversee the disposal of a large mixed cargo—from sugar, rice, coffee and tea to bedsteads and soap. Having sold these at good prices, he embarked in the small steamship Aurora on his return to India. This underpowered ship was wrecked on Gabo Island off Cape Howe on May 15, 1853, and Mackenzie was drowned. William Mackinnon was left alone to carry on the growing business in India. In fact. he was able to buy out his partner's brothers for Rs. 51.000, and it is of interest that these brothers went on to settle in Australia, where their direct descendants are active to this day.

Mackinnon was a small man with delicate features, but his commercial brain was razor-keen. To help him in his expanding mercantile business he brought out to India several young relatives and friends from his native Scotland. At the same time he was dreaming and planning for the expansion of trade by means of shipping. He saw clearly that the great potential wealth of the sub-continent could not be developed by railways alone, and that India could most easily get her goods into the world markets through a service of steamships that would open up innumerable small ports from Calcutta southwards and, round Cape Comorin, northwards to Bombay. He was in advance of his time in deciding that his steamships should be screw steamers, the propeller in preference to the side-paddle.

His chance came in the mid-1850s when the Hon. East India Company, then the effective government of both India and Burma, invited bids for a contract to carry mail between Calcutta and Rangoon on a strict schedule of regularity. Mackinnon was quick to make an offer; he would form a limited liability company to run at least two screw steamers

between the two great ports, the promptitude of their services guaranteed. This was accepted.

William Mackinnon then hurried home to Scotland to raise the necessary capital and buy the vessels he required. The Calcutta & Burmah Steam Navigation Co Ltd was registered in Glasgow on September 24. 1856. The capital was what we would regard nowadays as the modest sum of £35,000. It is of interest that Mackinnon reserved shares to the value of £7,500 fur sale to his friends in India.

That was the beginning of what is now the British India Steam Navigation Co and the anniversary of BI must date from the formation of the Calcutta & Burmah Company. It is of more than romantic interest that Mackinnon chose as the badge of his new concern — on crockery, cutlery, etc — the peacock of Burma.

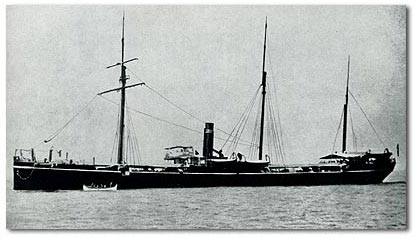

The first two vessels of the new company were the Baltic and the Cape of Good Hope. Both were screw steamers, but they were rigged as brigs, and the early steamship skippers never hesitated to hoist sail and so save coal in suitable conditions. Each was of about 500 tons gross, some 190 feet in length. It took these cockleshells months to sail from the UK to India round the mass of Africa.

Even so, they did well on the Burma mail run, the very first axis of BI services in Eastern waters. The mails were only a part of it. A tidy passenger trade developed, and in due course the cargo trade in such commodities as teak and rice grew so large that Rangoon became a base for

Mackinnon's ships second in importance only to Calcutta itself. Before the Second World War, for example, 20 vessels on eight different mail and passenger runs used the port: there was not a day of the week, except Sunday, when at least one BI ship was not coming in or going out.

Akyab and Moulmein were to become important ports of call for the ships with the two white bands round their black funnels. On what was known as 'the jungle run' they probed the tortuous channels of the Mergui Archipelago and, indeed, did much to chart, buoy and light those hitherto remote seaways. (The " Mutton Mail" was the regular Friday run from Calcutta to Rangoon and Straits, so called because the cargo included large numbers of sheep and goats.) In Moulmein they still remember the Ramapura and Rasmara, two paddle steamers specially designed to maintain a fast passenger service from Rangoon. These were Pan-ma-Hyno — "before the flowers fade," a pretty Burmese idiom, suggesting that the flower a girl might put in her hair in the early morning was still fresh when the ship arrived at its destination in the afternoon.

Indian Coastal Trade

In the meantime, William Mackinnon was rapidly expanding both his fleet and his trade. It was his conviction, shared in Government circles, that coastwise trade would be the solution of many of India's economic and over-population difficulties. So he sent his ships probing southwards towards Madras and Ceylon. Soon they were rounding Cape Comorin and heading northwards, so that Bombay became a terminal port of significance within the scheme of things.

This was a commercial revolution. Dozens of small ports along the Indian coasts were opened up to large-scale traffic — Vizagapatam, Coconada, Masulipatain, Tuticorin and so un. Artificial harbours were few and far between, of course, and even at Madras the loading and unloading was done by masula boats, those pliable craft that seem able to take any amount of knocking about and are so brilliantly handled by the local boatmen. Even more romantically, Mackinnon's ships became known along the seaboards of India as Chatri ki Jahaz, the Umbrella Ships, for if a local merchant had a parcel of goods to be put on board or taken off, he stood on a clear patch of beach and hoisted his coloured umbrella to catch the skipper's attention!

Within five years of the founding of the Calcutta & Burmah Company this shipping venture had prospered remarkably. The vessels were now venturing beyond Rangoon and Moulmein towards Penang and Singapore. A service was working, however infrequently, right round the sub-continent from Bombay to Karachi. A regular mail contract to cover the whole of this route was being negotiated, and Government was already hinting that it would like Mackinnon and his partners to undertake a similar service, eight times a year, up and down the Persian Gulf.

So William Mackinnon returned to the UK in 1861 and there, without difficulty, raised £400,000 to float the British India Steam Navigation Co Ltd — and the Calcutta & Burmah Company had been floated on only £35,000 six years before! Six new ships of size were promptly ordered from British yards. They were twice as large and twice as powerful as the Baltic and Cape of Good Hope of 1856. The new BI company was registered in Scotland on October 28, 1862.

The mercantile firm of Mackinnon, Mackenzie & Co, which William Mackinnon had formed with the friend drowned in shipwreck, became, as they are to this day, the Managing Agents, presiding over the fortunes of a great fleet from the towering office building in Strand Road, Calcutta.

Persian Gulf

The mail service of BI ships up and down the Persian Gulf started in 1862, and it was a step into the nearly unknown, into the dream-world of a modern film producer.

The Gulf, a sufficiently dangerous area in these days of radar and other navigational aids, was then virtually uncharted. The climate is highly variable from one end to the other—torrid heat below the Straits of Hormuz and then the killing shamal within. At one stage, even the deck officers of BI ships on the route threatened a sort of strike for better conditions on such a difficult tour of duty. Like their colleagues on the Calcutta-Rangoon-Singapore run, they had to do much of their own charting, buoying and lighting. The Persian officials on one side and the Arab dignitaries on the other were apt to be less than friendly to the invaders from Europe. There were always wild men about, carried as what were then called deck passengers — Afghans who had to be forced to surrender their arms on boarding the ships, and onshore pirates.

Usually the pirates could be driven off by hot water pumped by the engine-room through hoses, but the gang that looted the Cashmere in the late 1860s worked to an ingenious plan.

They embarked as deck passengers and, knowing the vessel to be carrying specie, rose at a signal. They succeeded in seizing the ship. and they got off with considerable booty after having killed an Indian engine-room hand and wounded several members of the crew, including the Third Officer. (It is a popular BI story that another officer, taking refuge on top of the awning, was heartily prodded from below by the scimitars of the pirates.) In the issue the then Sheikh of Muhommerah, a good friend to BI, hunted the bad men down, disposed of the ringleaders by hanging, and recovered much of the gold. It took much longer to persuade the Turkish Government to admit liability and pay compensation.

For many years thereafter every BI ship fired a salute as it passed the Sheikh's palace, near the site of the now historic oil town of Abadan.

The discovery of rich oilfields on the Arabian side of the Gulf has completely changed the picture from the shipping point of view. In the early days BI ships dealt mainly with the ports on the Persian side. For a long period of years the company ran a mail service all the way from London up to Basra. Now the needs of the new oil settlements at Qatar, Bahrein and Kuwait require a fast weekly service based on Bombay. This is maintained by four neat, modern vessels of the D Class — Dumra, Dwarka and their sisters, latterly reinforced by the larger Sirdhana.

Before the Suez Canal was opened in 1869 it was thought by many people that the mails from Europe to India and the East could best be handled by directing them to the Syrian coast, running them across country to the Euphrates-Tigris valley, and so down these great rivers to where the ocean-going ships waited at Basra. That was not to be. Just after the Second World War, however, BI services out of the Gulf were successfully expanded by the placing of ships mainly interested in cargo on a route that takes them from Basra all the way to Colombo, where they diverge either to Singapore, Hongkong and the ports of Japan, or to Australasia.

That is one measure of the ever-increasing importance of the Persian Gulf in the economics of our modern world.

Indian Labour Problems

Less than 20 years after it had been founded as the Calcutta & Burmah Co. the British India S. N. Co. Ltd. had become a formidable force in the shipping world. The ships listed in the company's handbook for 1873 numbered 31, running up to 1,780 gross register tonnage. Four new ones up to 2,500 grt were building. That was a big fleet for 1873.

It was not merely that the basic routes—Calcutta-Rangoon and beyond, Calcutta-Bombay, and Bombay-Basra —were doing well. The ships with the white-striped funnels were adventuring up towards China and Japan. There were explorations in the direction of Mauritius and the Seychelles. On occasion BI was asked to carry British troops so far afield as New Zealand. Small units of the Fleet circled the island of Ceylon.

The largest development towards the end of the nineteenth century, however, was that of the carriage of Deck or Unberthed passengers although circumstances have largely changed in these days.

Indian labour was looking for employment overseas. The labourers were ready and willing to work in the rice paddies of Burma, in the rubber plantations of Malaya. They would move far afield to the sugar plantations of the Pacific islands and even across that ocean to the West Indies. We know today that Indians, members of a clever mercantile race, form a large part of the confused racial mix of East and South Africa.

The British India company's business as a shipowner was to cater for this trade — to give the Indian worker a passage to his chosen field of labour at cheap rates and in decent circumstances. The ship specially designed to carry the Deck or Unberthed passenger was evolved. Most of this type of ship were working out of Madras across the Bay of Bengal to Burma and Malaya. Two of the specialised craft, Rajula and Rohna, at one time held the most comprehensive passenger certificates ever issued. Both vessels were authorised to carry more than 5,000 passengers—much more than the two great Cunard Queens were ever allowed.

This capacity of the older BI ships to carry a large number of passengers on any voyage was invaluable to Great Britain at various crises in her military history. But that is another story. It is sufficient meanwhile to note that, during its early years of expansion, the British India company operated exclusively in eastern waters, using Calcutta as its main base. The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 was to alter the whole pattern of the firm's trading.

The first vessel to pass northwards through the new Canal was the BI ship India, homeward bound to have her engines brought up to date.

The Southern Cross

The opening of the Suez Canal gave BI the opportunity of running for a while the longest mail service in the history of shipping—from London to Brisbane, Queensland. This voyage took fully two months to complete. The service was inaugurated by BI vessel, Merkara, which left London on February 12, 1881, and anchored in the approaches to the harbour of Brisbane on the evening of April 13 that year.

The history of BI's contacts with Australia in the later decades of the nineteenth century is curiously confused. Long before William Mackinnon founded his shipping company, he and his partner, Robert Mackenzie, had been speculatively trading with Australia during the fabulous days of the Gold Rush, shipping the consumer goods the new settlers required. It was not until the arrival of the Merkara, carrying immigrants and a cargo of refrigerating machinery, that a regular service was established.

The idea was largely that of Queensland's forceful Prime Minister, Sir Thomas Mcllwraith. He realised that emigrants from Britain, travelling by the conventional route south-about round Cape Leeuwin, were tempted to land at the first Australian port of call—Adelaide, Melbourne or Sydney—and he wished to attract to Queensland more than the riff-raff left at the end of the long voyage, not to mention the goods a community in the pioneer stage sorely required. Against bitter opposition, he therefore pushed through the Legislative Assembly a Bill to provide £55,000 a year for a mail Contract with BI

Unpopular as the arrangement may have been in the colony, as it was then, especially among the owners of small coastal shipping lines, it greatly benefited Queensland over a period of years. (It is on record that, when an emigrant ship arrived, she was immediately boarded by lone settlers looking for wives off the peg, so to speak). It was not, however, a great bargain for BI concern. The obligation to come into Brisbane north-about by Sumatra and the Torres -Strait, and home again by the same route, meant that the ships could rarely pick up for the homeward voyage the pay-load of cargo that might have been collected at the larger southern ports from Sydney round to Fremantle.

The direct London-Brisbane service petered out in 1895. BI had put on an adequate service from Calcutta to Queensland, but the ships from London had taken to coming south-about, getting the advantage of calls at Fremantle and other ports on the way. Economic troubles within Queensland itself checked the stream of assisted immigration.

For some time thereafter the story of BI's association with Australia is still more confused. The company's interest in the island continent had by no means abated, but it is a fair surmise that the Managing Agents in Calcutta were worried to know where to find the ships to meet the growing demands on the ramifying services they already provided over thousands of miles of ocean. More than one merger of shipping interests about the Australian coasts was arranged ; two Australian shipping companies of substance were acquired—the Ducal Line and the excellent little fleet of five vessels built up by Captain Archibald Currie.

The latter had built up an interesting trade. Currie specialized in the carriage of Australian horses—the famous brumbies mainly for the use of the Indian Army ; and he carried back to Australia large cargoes of gunnies, that is, jute bags for wheat and so on. (He once carried a load of 400 camels from Karachi to South Australia). The loading and unloading of a cargo of spirited horses was apt to create pandemonium, just as the high spirits of the dealers who accompanied their animals made any voyage in a BI ship from Australia to India a very lively social affair indeed.

Watering the horses at sea presented a problem that had to be solved by careful trial and error. It was discovered that if the grooms started at one end of the stalls, hell in the shape of flashing hooves and tossing heads was let loose at the other. Thus it was found necessary to see that the buckets were evenly distributed over the decks before watering started. It is on record that horses in transit relished an occasional ration of draught beer.

The most dramatic among the many legends of BI comes out of its Australian associations. This was the wreck of the Quetta on the hitherto uncharted rock that now bears her name.

She was homeward bound and with a Torres Strait pilot embarked when she struck the reef on the night of February 28, 1890. She sank within three minutes, and the loss of life was heavy. Among the survivors was a baby girl, and it was long enough before her identity was established. She was taken into the household of Captain Thomas Brown, a Torres Strait pilot, and brought up as Quetta Brown. On Captain Brown's death the child was adopted by his brother. Villiers Brown, of Brisbane, and in due course she married his son. This young man was killed in the First World War, and Quetta Brown ultimately took a second husband in Mr. Malcolm McDonald of Brisbane, where she died in 1949.

It is now known that she was the only child of a widower, Copeland by name. who had himself been accidentally drowned not long before, and that she was being sent home to relatives in England. There is still a Quetta Memorial Chapel on Thursday Island. There to this day hangs the ship's bell.

The BI services to and from Australia were interrupted by the two World Wars, but they are now on a firmer footing than they have ever been before. In conjunction with the vessels of the P&0 and Federal Companies, three BI ships with refrigerated space are on the regular UK-Australia route by way of Mediterranean and Red Sea ports. Another service from the Persian Gulf carries passengers and goods for the island continent, touching at Karachi, West Coast of India ports and Ceylon. A third service runs from East Coast ports of India and Pakistan, touching at Colombo and Singapore on the way. The three services circle the huge island, both by the Torres Straits and Cape Leeuwin.

It is of interest that, on the first of these routes, BI chooses to employ its two fine Cadet Ships, Chindwara and Chantala, each accommodating a score and more young men in training as officers. High-spirited in the way of youth, they are familiar visitors from Brisbane round to Fremantle.

Darkest Africa

The intricate pattern of the British India company's trading in Eastern and Southern waters was completed when it made a connection with East Africa — a connection that, after many vicissitudes, is today in excellent condition.

It was in 1872 that Government contracted with the company for a mail service between Aden and Zanzibar. In general in those days the mails from the UK were carried out of London by the fast ships of the P&0UK Their distribution to the more remote ports of the Indian Ocean, the Bay of Bengal and beyond became the responsibility of BI

The British Government had a twofold purpose in East Africa. It was pledged to the suppression of the slave trade. On a lower level, it had to keep a sharp eye on the intrusions of the new German imperialism, then carefully exploring and quietly annexing the coastal regions of a potentially rich hinterland. Thus the British India company and its Chairman, by now Sir William Mackinnon, Bart., had become deeply involved in matters of political as distinct from purely shipping interest.

The mail Contract in itself was not an attractive bargain, but East Africa was then in an early stage of development, and at Aden BI ships could take over from the larger P&0 vessels all manner of manufactured goods from Europe and the States. They could bring back the typical products of the region—coconut in various forms, cloves and rare timbers. The company's services were extended southwards down the coasts of East Africa to Portuguese East Africa, there only to meet the opposition of what is now the Union-Castle line.

Early representatives of BI in East Africa had many queer problems to face. They were called upon to deal in ivory and rubber, reckoning their accounts in sterling. Maria Theresa dollars, and then rupees and cents. They had to supply a bottle of blotting sand for an Arab princeling, a double-barrelled gun for King M'tesa of Uganda, a variety of goods for the Queen of Madagascar. One indent of 1879 shows them bringing in a quantity of fish-hooks, 3.000 Tower muskets, a second-hand safe and 30 copies of the Koran, five of these in expensive binding.

It is to cut a long story short to say that, on the purely shipping side, the extension to East Africa was of great advantage to BI. From Zanzibar, the first base, the ships visited the Seychelles, Mauritius and Reunion. A regular service took to running from Zanzibar by way of the Comoro Islands to Madagascar. Another swept right round the Indian Ocean from Bombay to Aden. Aden to Zanzibar, and so southwards to Mozambique and Delagoa Bay.

Thus the little shipping concern founded by William Mackinnon in 1856 was straddling the seas East of Suez, here, there and everywhere. In 1894 the Fleet consisted of 88 vessels, some of them running up to 5,000 tons gross—even more in the case of the Golconda, an old-timer that survived until torpedoed in the North Sea in 1916.

The political circumstance that involved BI company and its directors in the public affairs of East Africa was the formation of the Imperial British East African Company. This followed the agreement of the British Government to hold a protectorate over Zanzibar. The IBEA was to explore and develop the interior as well as to put down slavery and strong drink, and to promote religious freedom. It was also to survey the line of the Uganda Railway far into the interior from Mombasa. where BI had already set up a new base for its purely shipping operations. Of the capital of £240.000 William Mackinnon, his relatives and associates put up fully one-quarter.

The venture did not prosper. Caravans of native labourers were lost or massacred in the backblocks, goods looted right and left. Experiments in growing coffee and flax were expensive failures, as were groundnuts many years later. Within just a few years its funds began to run out.

At the highest level Sir William Mackinnon intimated to the British Government that, unless financial help was forthcoming, the IBEA must close down at the end of 1892 and abandon both Kenya and Uganda — probably to the Germans. He suggested a subsidy of only £50,000 to continue the administration of Uganda for five years. It was refused. William Mackinnon died in London in June, 1893.

One of the best friends of his later years was H M Stanley, the author-explorer. A rigid member of one of the most severe Presbyterian denominations, William Mackinnon was deeply interested in the African work of David Livingstone, and when his body at length came down from the interior, it was laid out in what is still BI flat above the office of the agency in Zanzibar. It was then reverently carried to Aden in a BI vessel for transhipment by P&0 to London and Westminster Abbey. When Stanley was setting out on his expedition to relieve Emin Pasha. Mackinnon put at his disposal BI ship Madura to carry its personnel and supplies from Zanzibar round the Cape to the mouth of the Congo.

Stanley was at hand when William Mackinnon died in the Burlington Hotel. London. He attended the funeral on the estate his friend had bought for himself in the West Highlands of his native Scotland. He insisted in his copious writings that the refusal of the Government to help the IBEA was the death-blow.

That is as may be. Mackinnon was already 70 years of age and had endured a long and often worrying career in the shipping business. It was of more importance now that the British Government came to its senses after his death and took the East African problems in hand. The railway from Mombasa right up to Nairobi was duly completed. Out of the welter of international politics the East African regions were saved for the British Commonwealth and it is now proper to understand that the vision and investments of this little man from Campbeltown have prevailed where a British Government looked like failing.

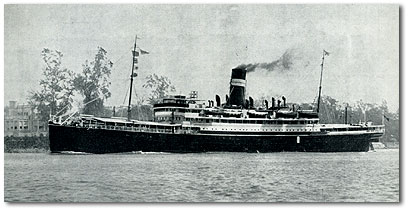

William Mackinnon has many memorials, the best of them, artistically, the statue in the Treasury Gardens at Mombasa. But better still is the ebb and flow of BI ships out and in the East African ports, the procession always led by the queens of the modern fleet, the Kenya and Uganda, of 14,500 gross tons each, maintaining the regular fast mail service between London and ports as far south as Beira.

Inchcape the Great

It is more than 60 years since William Mackinnon died but except in the Bay of Bengal area and on the Coast of India, the pattern of BI trading has remained largely unchanged.

In the Bay of Bengal area BI pre-war maintained a network of passenger and mail ships. In addition they catered with cargoships for the major share of the rice trade from Burma to India and Ceylon and the coal trade from Calcutta to Indian coastal ports, Burma and Ceylon. In 1938 BI carried over 500,000 passengers and nearly 950,000 tons of cargo in these passenger and mail ships, over 800.000 tons of cargo from Burma in the cargoships and well over 1,000,000 tons of coal from Calcutta.

Today most of these trades are non-existent for BI but the major overseas services of the company still run on the lines that were already familiar when Queen Victoria celebrated her jubilee. Ships run regularly from the UK through the Mediterranean, the Suez Canal and the Red Sea. spreading fanwise over the reaches of the Indian Ocean, the Bay of Bengal and down to Australia. Local services based on Calcutta and Bombay — each of these ports with its BI dockyards and repair shops — provide services from the East to China, Japan, Africa and the Persian Gulf.

Nor did the death of the founder of the company involve the slightest halt in its development. From the very beginning BI has created its own civil service, so to speak. Likely young men are selected to go to head office of the managing agents in Calcutta, there to go through the mill and to proceed, if their merit is proved, to one or other of the main agencies: anywhere from Karachi to Yokohama. Some fall by the wayside, as they do in any navy or army, but there is always a majority of tried and trusted men to carry on in the tradition established by Mackinnon and his associates 100 years ago.

On the founder's death in 1893 the chairmanship of the company was taken over by his oldest, ablest and most faithful friend in business, James Macalastair Hall. This was only for a year until, in 1894, Sir William's nephew, Duncan Mackinnon. took the seat of honour: the founder having died childless.

In the meantime, however, a particularly bright star had arisen in the East. This was James Lyle Mackay, latterly the first Earl of Inchcape, and beyond any doubt far and away the most forceful among the many forceful figures produced by the British shipping industry.

A native of the seaport town of Arbroath in the Scottish county of Angus, his father the captain-owner of sailing ships, he went to India as an assistant with Mackinnon, Mackenzie & Co in 1874. Five years later there occurred a crisis within the Bombay agency, when the affairs of the then agents. Nicol & Co, got into a mess. Mackay was sent across the subcontinent to clear up the confusion, and this he did with ruthless brilliance. When he returned to Calcutta in the late 1880's he was the supremely able man in complete charge on the spot; and all the nominal powers of a chairman and board of directors in London could not stay his triumphant handling of BI aftairs. He was now the managing director of the managing agents— and he managed.

The story of a remarkable life is told in the authorised biography — Lord Inchcape by Hector Bolitho. But however large and important the many affairs he handled for the British Government, and even if he was almost nominated Viceroy of India and was actually offered the throne of Albania, BI was his first and last love. He was almost entirely responsible for the merger of the P. & 0. and BI interests in 1914, but he was the last man to allow the identity of the younger concern to be lost in that of the older. The colours, the funnel-markings and the traditions dating from 1856 must be maintained; BI Fleet must be kept in perfect trim, growing in size and efficiency as its special trades required and as shipbuilding science advanced.

Lord Inchcape became Chairman and Managing Director of the huge P&O/BI group when the merger took place. That was almost on the outbreak of the First World War, and his companies were immediately plunged into dangerous action. The BI ships, with their specialised capacity for handling many hundreds of unberthed passengers at one time, were invaluable as troop carriers and as hospital ships. Losses were heavy — and they were to he very much heavier in the Second War—but such was Inehcape's prescience in buying tonnage and arranging amalgamations, that in 1922 BI Fleet was the largest single merchant fleet in the world — 158 vessels of nearly a million gross tons afloat and in regular service.

This man's genius in the larger affairs of shipping is implicit in the tale of just a few of his acquisitions in the face of competition from Japanese and German interests. He bought the Nourse Line with its regular services from India to the West Indies by way of South African ports. He was quick to acquire the Apcar Line when the Armenian family of that name decided to dispose of its highly efficient service from Calcutta to Japan. And it is of much historical interest that the local merchants at intermediate ports, and particularly at Hong Kong, still refer to the service as the Apcar Line.

The first Earl of Inchcape died in 1932. He was succeeded as head of the Board by his son-in-law, the Hon. Alexander Shaw, who became in due course the second Baron Craigmyle. This Lord Craigmyle was a man of the sharpest ability, but his health was poor, and after six years in the chair he retired.

To the oversight of the great P&O/BI group there was then appointed Sir William Crawford Currie, GBE, who has continued as Chairman to this day and who will preside over the celebrations of this centenary occasion.

Sir William was born into the BI, so to speak, his father a kinsman of the Mackinnons and a partner of Mackinnon, Mackenzie & Co in due course, after going through the mill. Sir William was educated in Scotland and at Cambridge, qualified as a chartered accountant in Glasgow, and in 1910 followed the family trail to Calcutta as an assistant, to become a partner in 1918 and eventually senior partner. In 1926 he was called to the London office and in 1932 became deputy chairman of the P&O/BI group. Elected chairman six years later he was, like Lord Inchcape before him, left to handle the affairs of this huge concern during a Second World War, at the same time working for Government as Director of the Liner Division of the Ministry of War Transport.

BI ships were sunk by the dozen in that bitter Second War. the terrors of dive-bombing and guided missiles added to the threat of the conventional U-boat. In all, 51 vessels grossing 351,756 tons were lost in the struggle—and that was almost one-half of BI fleet wiped out. Sir William Currie was left with the task of rebuilding anew, also to face the many problems created by the grant of independence to India, Pakistan and Burma.

Those tasks have been faced, the problems overcome. In this centenary year the BI fleet consists of 60 vessels with a total gross tonnage of 432,722. Five new ships are being built or fitted out — up to the giant Nevasa of 20,000 tons, designed as a troopcarrier under the company's management. Five large oil-tankers will be added before the end of this decade. In an average year the British India company's ships carry some 3.5 million tons of cargo and nearly 300,000 passengers over three million nautical miles of sea-routes.

The body of William Mackinnon lies in a remote graveyard in the West Highlands of Scotland, at Clachan, Argyll, near his beloved house Balinakill. His soul goes marching on.

(Editor's note: The author of this history, which appeared in a company-issued booklet, is unknown. With a view to publishing a correct attribution, the editor would be pleased to hear of anyone who believes they have a claim to the copyright of this work.)

Other history pages: Timeline | Companies | Routes | BI News |Mercantile Empire | BI/P&O Merger document | Gairsoppa & Mantola | Dara wreck | Rohilla disaster | Rohilla Centenary | Calabria | Abhona trials | E Africa Shipwrecks | Today in History